No. 1 Heavy DRI: Scrap Rival or Enhancer?

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Direct From Midrex thanks Michael Marley for allowing us to publish remarks he made at the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI) Convention in Las Vegas earlier this year. Mike worked with us to update the information to capture the pulse of the steel and scrap industries through the summer and into the fall.

I’ve spent almost 40 years on the scrap heap. I’m not a junk car or discarded washing machine. I’ve reported scrap prices and market trends for a few trade publications like the now-deceased Iron Age magazine and the still alive and thriving AMM. Today, I write a weekly newsletter with the eponymous name of Mike Marley’s Shredded Power. That’s a name bestowed on it by my boss, steel industry analyst Peter Marcus of World Steel Dynamics.

While covering the ferrous scrap beat, I frequently talk to traders and buyers about other steelmaking raw materials like pig iron and direct reduced iron (DRI). In those discussions, DRI is often called a competitor or substitute material for ferrous scrap. During one such recent chat with long-time Midrex analyst Robert Hunter, he said something that struck me as insightful and different from what I often hear from others. If anything, he said, DRI is a complementary material that has enhanced and supported the use of ferrous scrap and not displaced it. There is much to think about in that light when you consider the history of DRI in the U.S. and other steelmaking countries, the current ferrous scrap market and the revived interest in DRI. What has driven that rebirth and what are some of the changes it could bring about?

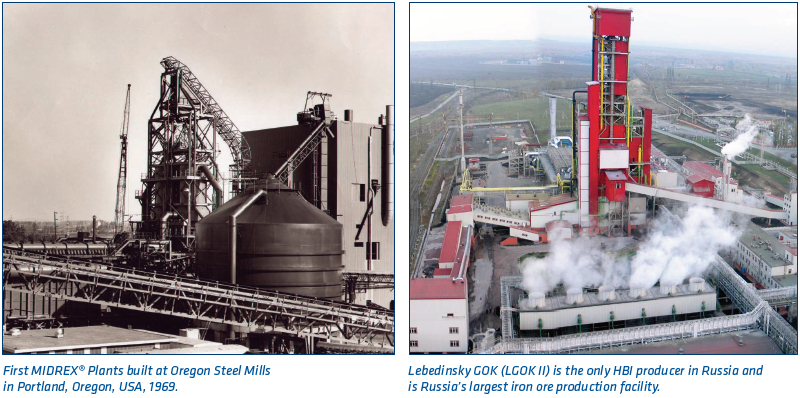

Midrex didn’t invent direct reduction technology. It wasn’t even called Midrex in those days. It began with a company called Surface Combustion Corp. in the 1960s. German steel whiz Willi Korf acquired the technology from Surface in the 1970s and launched Midrex as a designer and developer of DRI plants. The technology has been widely used in developing countries that have been blessed with abundant supplies of natural gas. Prior to the introduction of technologies like direct reduction, much of that gas had little or no value in some countries, unless someone was willing to build a pipeline long enough to carry it to the developed world. Oil companies flared it off in many regions.

What Midrex and its rival DRI builders did was to persuade the gas-rich countries like those in the Middle East and Venezuela to use that energy to make iron and from that iron, they could make steel products like rebar and I-beams to be used by their nascent construction industries.

Midrex found a few risk takers in the U.S. who liked the idea of an alternative iron source. These included mills like Oregon Steel Corp. in Portland, OR and Korf’s own wire rod mill in Georgetown, SC. Before they could prove the worth of DRI, these plants were victimized by surging natural gas prices. They subsequently disappeared. Indeed, during my tenure as editor of Iron Age, I visited Oregon Steel in the 1980s and toured the steel plant. When we got back to the corporate offices after the tour, I asked one of the company’s executives where was their famous DRI plant. It was the first one built in the U.S. He pointed to an empty lot across the street. “It was there till we scrapped it,” he said.

There wasn’t another such risk taken in the U.S. until the 1990s, when American Iron Reduction built a DRI plant in Louisiana. But that was ill-timed as well. It failed and was sold. The buyer? Nucor Corp., the biggest ferrous scrap consumer in the U.S., if not the world. Nucor executives had the good sense to dismantle the plant and move it to Trindad and Tobago, where there are ample supplies of natural gas available at a reasonable cost.

One country where DRI achieved success, at least until a few years ago, was Venezuela, an oil and gas rich nation. It built several captive plants for its own steel industry, as well as merchant DRI/HBI facilities that sold their output to steelmakers in the U.S. and elsewhere around the world. Many of these operated well until the “pink tide” of Latin American Marxism led by the Lt. Col. Hugo Chavez destroyed their efficiency and reliability. It was not unusual to hear buyers at several U.S. mills complain in the past decade because cargoes of HBI from Venezuela were several months, not weeks, late in arriving. The future prospects for DRI production in the U.S. were dim after that. Even the reliability of other offshore suppliers was sometimes in doubt as well.

Then came fracking and its impact on both the supply and price of natural gas. Again, credit Nucor with being bold enough to recognize that opportunity and install a new DRI plant in the U.S., the first in almost 20 years. Back in 2013, before it came onstream in Convent, LA, I spoke at the ISRI Ferrous Roundtable in Chicago and wondered aloud whether it would herald busheling’s last hurrah. I was reaching too far at the time, trying to provoke a reaction from the audience.

Busheling is still the main melt material for all of the EAF-based flat-rolled mills and others that make formable products like wire rod. But I don’t think it would be too bold to say that Nucor’s Convent plant has influenced the pricing of prime scrap. Their DRI plants have played a role in minimizing Nucor’s appetite for industrial steel scrap and is now helping it to meet the new demand for hot-rolled band from some of the domestic industry’s integrated steel mills that have shut down about 5 million tons of their raw steelmaking capacity in the past year.

Nucor chief executive John Ferriola boasted to industry analysts that its use of DRI took about $100 per ton off the busheling price last year. Now that was a bold claim! Other forces may have had a role. These include the strong pace of auto output, which produces more new steel scrap as well as more cars and trucks, competition from cheap foreign steel, at least prior to the U.S. Commerce Department’s decision to impose anti-dumping and countervailing penalties on some overseas steelmakers, and the diminished scrap demand from the integrated mills because of cheaper iron ore prices and the steelmaking capacity cutbacks.

When Nucor-Convent came onstream, some scrap dealers assumed it would provide a substitute for imported pig iron. They were certain Nucor was only concerned about its dependence on offshore supplies of raw materials, much like some U.S. integrated steel producers were in the middle of the last century. After spending millions of dollars to develop iron mines in Venezuela, some major U.S. steel corporations abandoned those facilities and chose to remain wholly dependent on the ore mines in northern Minnesota and Canada. Ironically, dependence on offshore steel supplies was the basis for Nucor’s decision to first get involved in steelmaking back in the 1960s.

When thinking about what DRI plants produce, it’s important to realize they actually make two products, not one. The first is iron; the other is leverage. That can’t be weighed or loaded on a barge like the DRI pellets, but it is there nonetheless. In other words, steelmakers and the people that buy scrap for their mills use it as a bargaining chip during the buy week each month, in much the same way that they uses imports of scrap from Europe and pig iron from Brazil and eastern Europe. In other orders, their scrap brokers and buyers might say that instead of buying 3,000 tons of busheling from dealer X this month, the mill only needs about 1,000 tons and will pay $10 per ton less than last month’s price.

Being stuck with 2,000 tons of unwanted busheling is a serious problem for dealers handling mainly industrial scrap, especially if they are likely to face that same problem next month and the month after that. Scrap dealers can’t cut off the flow of industrial scrap by reducing their buying price for that scrap. That works for junk cars that they feed into their shredders, but automotive stampers and other manufacturing plants keep filling up those roll-off containers expecting them to be picked up promptly regardless whether the price of busheling is $800 per ton, as was the case in 2008, or $150 per ton last December.

Steel Forgings

When the busheling prices dropped that low in scrap-rich regions like Detroit and elsewhere in the industrial Midwest, DRI was no longer the bargain it had been. Nucor said in January that it would halt production at Convent. That hiatus didn’t last very long. Two weeks, I believe. Some observers believe a spike in demand for hot-rolled coils, not only from domestic steel users but also by the now hot metal short integrated mills, may have accounted for the change. The EAF flat-rolled mills now euphemistically refer to those sales as the “substrate” market. Integrated mills now buy hot-rolled coils from their EAF flat-rolled rivals and turn it into cold-rolled and galvanized sheet steel. So much for the argument that only blast furnace should be used to make these products.

Prior to the rebound in domestic sheet sales and prices, demand and prices of scrap had fallen for five months in a row in the second half of last year. Prices were off by more than 50 percent from the levels seen at the start of 2015. Such steep cuts do not affect the flows of industrial scrap, but they do impact the intake of obsolete scrap at dealers’ yards.

The demolition business dried up, auto wreckers started piling up flattened cars in the back of their yards instead of selling them to shredders and peddlers stopped dumpster diving and vanished. If a dealer was only paying $40 per ton for old appliances and what some call “alley scrap,” it was no longer worth the time to drive around and collect that material. Many peddlers operate with old half-ton pickup trucks. If they get only $20 for a load of old scrap, that didn’t even cover the fuel cost in these now cheaper energy days.

But times changed yet again! And it had nothing to do with an old Bob Dylan song. The domestic flat-rolled mills got a late Christmas present: The Commerce Department decided that much of the imported sheet steel was being sold at unfair prices in the U.S. and decided to impose anti-dumping and countervailing duties that would level the playing field. That sent many domestic steel consumers and service centers looking for more sheet from U.S. mills.

Two other forces were at work at the same time. First, as noted earlier, two integrated steelmakers cut raw steel production at some of their mills. These included U.S. Steel Corp’s mills in Fairfield, AL, and Granite City, IL and AK Steel Corp.’s mill in Ashland, KY. In fact, AK Steel said at one time that it would no longer pursue the commodity hot-rolled sheet business. That forced these integrated mills, as well as the steel consumers and warehouses, to turn to the domestic flat-rolled mills.

Secondly, overseas demand for ferrous scrap revived briefly in March and April. This involved stronger demand and higher prices from steelmakers in Turkey, the world largest importers of ferrous scrap, as well as more buying by steelmakers in Taiwan and other nations in southern and southeastern Asia. Much of this was spurred by a spike in steel billet prices in China and decisions by some Chinese steel exporters to withhold billet supplies when overseas steel buyers balked at paying the higher prices.

This put new pressure on some domestic EAF flat-rolled mills in the second quarter. Prices rose by between $10 and $15 per ton in the first week of March. But by mid-month, several of the major EAF mills were reaching out to scrap suppliers in distant regions and paying what scrap dealers and steel mills call “springboard prices.” Some paid premiums of as much as $50 per ton over the prices they were paying their local suppliers for the same grades of scrap. These premiums reflected higher F.O.B. or shipping point price paid to the remote dealers that matched or surpassed what they were getting from mills in these regions, as well as higher rail and barge freight transport costs. This upward trend continued into midsummer, with some flat-rolled mills in the South paying as much as $305 per ton for desperately needed tons of busheling and bundles. It eased in August when, thanks to the stronger U.S. dollar and the Brexit crisis in Europe, some U.S. EAF sheet producers were able to buy several cargoes of bundles from European exporters.

"THE DOMESTIC FLAT-ROLLED MILLS GOT A LATE CHRISTMAS PRESENT: THE COMMERCE DEPARTMENT DECIDED THAT MUCH OF THE IMPORTED SHEET STEEL WAS BEING SOLD AT UNFAIR PRICES IN THE U.S. AND DECIDED TO IMPOSE ANTI-DUMPING AND COUNTERVAILING DUTIES THAT WOULD LEVEL THE PLAYING FIELD."

So in light of later market developments, Nucor’s sudden about-face on idling the DRI plant in Convent doesn’t seem as surprising. Besides the benefit of the favorable trade rulings, the ongoing strength of the domestic auto sales and the automaker demand for sheet steel are the fundamental drivers for the market.

It’s a safe bet that Nucor won’t be abandoning that DRI plant in Louisiana anytime soon, even if offered busheling at $100 per ton. The company won’t stop using prime industrial scrap either, but it won’t be as dependent on that material as it has been in the past.

It would be foolish for Nucor to free up a lot of industrial scrap supply for its rivals, in particular for the new Big River Steel mill expected to come onstream in Arkansas later this year. I believe there are other steps the steelmakers could take to achieve that, such as trading iron ore futures to minmize their exposure to the ups and downs of pricing in that market. But Nucor in the past has indicated its opposition to futures trading in hot-rolled coil and may be rejecting any role in the futures trading of steelmaking raw materials like ferrous scrap and iron ore to avoid being forced into accepting hot-rolled coil contracts by some of its customers.

It is unclear whether the costs or lack of capital has deterred other steelmakers from considering construction of new DRI plants. It hasn’t discouraged voestalpine, the Austrian steelmaker and steel equipment supplier. Its new DRI plant in Texas will ship half of its output home to its mills in Europe and the rest to Mexican and U.S. steelmakers.

There is still some talk about others building DRI facilities next to existing steel mills or as possible merchant facilities linked to one or more of the iron ore mining companies. The steel industry has seen several “me too” projects pursued after an innovator like Nucor succeeds. Even former Nucor chairman Daniel DiMicco suggested at one time that the company could add a second module in Louisiana and become a merchant producer. Nucor could supply all of the U.S. steel mills that have been frustrated by the erratic behavior of the merchant ironmakers in Latin America. Now that they have acquired a taste for Nucor and other EAF mills’ hot-rolled coil, they might respond to such an offer with a polite “thanks, but no thanks.”

There is also the possibility that some of the cash-strapped integrated mills might restart part of the hot end of their idled facilities if an iron miner built a merchant plant or two to supply them with DRI. They would not need the coke ovens and blast furnaces and could avoid the current expenses for relining some furnaces and the potential future costs like a carbon tax. If not, the alternative might be a possible takeover or partnership with a foreign steelmaker. One such scenario might involve a Chinese steelmaker buying an American mill and shipping slab or hot-rolled coil made in China with cheaper Australian iron ore. U.S. Steel Corp has such an arrangement with Posco, the big South Korean steelmaker. Posco has been shipping hot-rolled coils to a U.S. Steel cold mills in Pittsburg, CA, for more than 20 years.

One final thought, and this ties in with Robert Hunter’s notion that DRI enhances scrap usage and does not displace it. What’s to discourage some rebar and structural mills in the U.S. from using DRI? They do it in the Middle East. The point is simply this: DRI’s higher iron content could pave the way for some of these mills to use less desirable but cheaper grades of ferrous scrap. This could include grades like mixed machine shop turnings, which some already use, and, Heaven forbid, even the dregs of the ferrous scrap supply pipeline—burned muni scrap.

Or, and this is purely speculative, what about as another raw material stream when shredded scrap is in tight supply, as has been the situation at times this year when DRI was available at lower or competitive prices? Several of the long products mills tapped the busheling supply last year when shredded was tight. Busheling and bundles were plentiful and available at cheaper prices. This was perhaps the longest period in which busheling and shredded prices were upside down, as some in the scrap and steel industry might say, or in backwardation, to use commodities markets language. They were that way for close to a year in several key steelmaking cities like Chicago, Detroit and Cleveland.

Again, these are just speculative ideas, or perhaps I should say, they seem to be at this time!